Storms on Saturn's Titan

Storms in the Tropics of Titan

© Gemini Observatory/AURA/Henry Roe, Lowell Observatory/Emily Schaller, Insitute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii

|

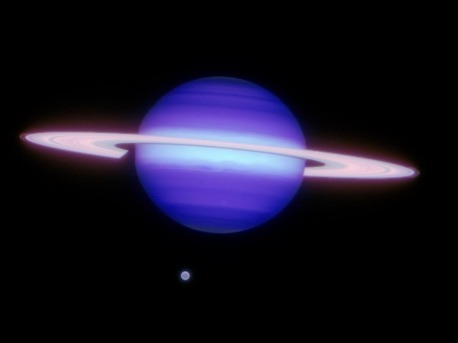

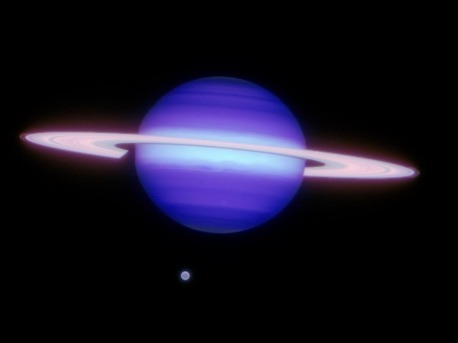

Infrared image of Saturn and Titan (at about 6 o'clock position).

However, just because weather occurs "infrequently" doesn't mean it never occurs, nor does it mean that astronomers, in the right place at the right time, can't catch it in the act.

That's just what Emily Schaller and colleagues accomplished when they observed, in April 2008, a large system of storm clouds appear in the apparently dry mid-latitudes and then spread in a southeastward direction across the moon. Eventually, the storm generated a number of bright but transient clouds over Titan's tropical latitudes, a region where clouds had never been seen - and, indeed, where it was thought they were extremely unlikely to form.

"A couple of years ago, we set up a highly efficient system on a smaller telescope to figure out when to use the biggest telescopes," Brown says. The first telescope, NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility, on Mauna Kea, takes a spectrum of Titan almost every single night. "From that we can't tell much, but we can say 'no clouds,' 'a few clouds,' or, if we get lucky 'monster clouds,'" he explains.

"The first cloud was seen near the tropics and was caused by a still-mysterious process, but it behaved almost like an explosion in the atmosphere, setting off waves that traveled around the planet, triggering their own clouds. Within days a huge cloud system had covered the south pole, and sporadic clouds were seen all the way up to the equator."

The images snapped by the Huygens probe in January 2005, as it descended through Titan's soupy atmosphere and toward the surface, revealed small-scale channels and streams, which looked just like features created by fluids - by water, here on Earth, and on Titan, probably by liquid methane.

Experts had speculated for years on how there could be streams and channels in a region with no rain. The new results suggest those speculations may prove unnecessary. "No one considered how storms in one location can trigger them in many other locations," says Brown.

Storms on Saturn's Titan

Storms in the Tropics of Titan

© Gemini Observatory/AURA/Henry Roe, Lowell Observatory/Emily Schaller, Insitute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii

|

Infrared image of Saturn and Titan (at about 6 o'clock position).

However, just because weather occurs "infrequently" doesn't mean it never occurs, nor does it mean that astronomers, in the right place at the right time, can't catch it in the act.

That's just what Emily Schaller and colleagues accomplished when they observed, in April 2008, a large system of storm clouds appear in the apparently dry mid-latitudes and then spread in a southeastward direction across the moon. Eventually, the storm generated a number of bright but transient clouds over Titan's tropical latitudes, a region where clouds had never been seen - and, indeed, where it was thought they were extremely unlikely to form.

"A couple of years ago, we set up a highly efficient system on a smaller telescope to figure out when to use the biggest telescopes," Brown says. The first telescope, NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility, on Mauna Kea, takes a spectrum of Titan almost every single night. "From that we can't tell much, but we can say 'no clouds,' 'a few clouds,' or, if we get lucky 'monster clouds,'" he explains.

"The first cloud was seen near the tropics and was caused by a still-mysterious process, but it behaved almost like an explosion in the atmosphere, setting off waves that traveled around the planet, triggering their own clouds. Within days a huge cloud system had covered the south pole, and sporadic clouds were seen all the way up to the equator."

The images snapped by the Huygens probe in January 2005, as it descended through Titan's soupy atmosphere and toward the surface, revealed small-scale channels and streams, which looked just like features created by fluids - by water, here on Earth, and on Titan, probably by liquid methane.

Experts had speculated for years on how there could be streams and channels in a region with no rain. The new results suggest those speculations may prove unnecessary. "No one considered how storms in one location can trigger them in many other locations," says Brown.