Exoplanets

How do we know that planets exist outside our Solar System?

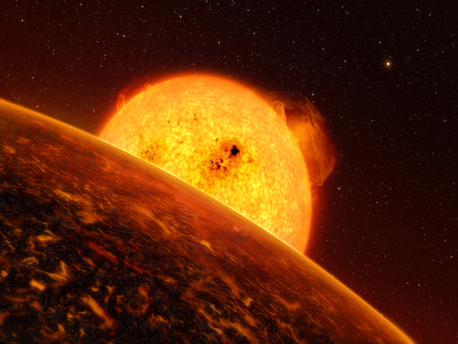

© ESO/L. Calcada

|

In early February 2009, the CoRoT space telescope discovered CoRoT-7b, the first rocky planet to be detected outside the solar system (artist’s impression). CoRoT-7b is five times heavier than our home planet and has approximately the same density. This extra-solar planet therefore belongs to the class of ‘Super Earths’ – of which about a dozen are known – although this is the first time it has been possible to determine the density of one of them. CoRoT was launched on 27 December 2006 from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan and is the first satellite mission to be tasked with searching for rocky – this is, Earth-like – planets outside our Solar System.

Since 1995, over 370 exoplanets have been found – and there appears to be no end to the discoveries. Although astronomers have now succeeded in making a direct optical verification, two indirect astronomical measuring techniques have been shown to be particularly reliable in the search for exoplanets: the ‘radial velocity’ method and the 'transit' method.

Methods to verify the existence of extrasolar planets

The radial velocity method is based on the premise that a star and the planet orbiting it have a reciprocal influence on each other due to their gravity. For this reason, the star moves periodically (in synchrony with movement of the planet around it) a little towards the observer and a little away from the observer along the line of sight. Due to the Doppler effect, in the electromagnetic spectrum of the star a radial movement such as this leads to a small periodic shift in the spectral lines – first towards the blue wavelength range, then back towards the red. If we analyze this movement of the spectral lines quantitatively, what is known as the radial-velocity curve can be derived from it. This yields parameters for the planetary orbit and the maximum mass of the planetary candidates. If the latter is less than the mass that a heavenly body requires to initiate thermonuclear fusion, the body is regarded as a planet.

The transit method works if the orbit of the planet is such that, when viewed from the Earth, it passes in front of the star. During the planet’s passage across the star disk, known as a transit, the planet’s presence reduces the amount of radiation from the stellar disc that reaches the observer and a decrease in the apparent brightness of the star can be measured. The radius of the planet and its density can be calculated from these measurements together with other data (such as the distance of the star from Earth) – astronomers then know whether the planet in question is a rocky planet or a gas planet. Such findings are incorporated into models of how planets are formed and help us to better understand how planetary systems develop.

German Aerospace Center

Exoplanets

How do we know that planets exist outside our Solar System?

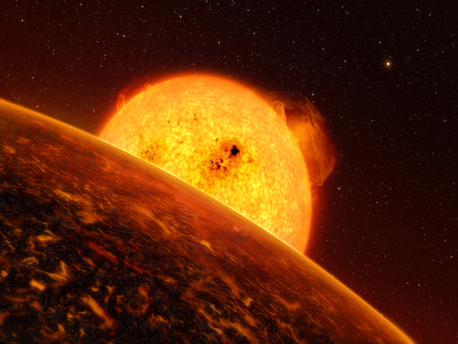

© ESO/L. Calcada

|

In early February 2009, the CoRoT space telescope discovered CoRoT-7b, the first rocky planet to be detected outside the solar system (artist’s impression). CoRoT-7b is five times heavier than our home planet and has approximately the same density. This extra-solar planet therefore belongs to the class of ‘Super Earths’ – of which about a dozen are known – although this is the first time it has been possible to determine the density of one of them. CoRoT was launched on 27 December 2006 from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan and is the first satellite mission to be tasked with searching for rocky – this is, Earth-like – planets outside our Solar System.

Since 1995, over 370 exoplanets have been found – and there appears to be no end to the discoveries. Although astronomers have now succeeded in making a direct optical verification, two indirect astronomical measuring techniques have been shown to be particularly reliable in the search for exoplanets: the ‘radial velocity’ method and the 'transit' method.

Methods to verify the existence of extrasolar planets

The radial velocity method is based on the premise that a star and the planet orbiting it have a reciprocal influence on each other due to their gravity. For this reason, the star moves periodically (in synchrony with movement of the planet around it) a little towards the observer and a little away from the observer along the line of sight. Due to the Doppler effect, in the electromagnetic spectrum of the star a radial movement such as this leads to a small periodic shift in the spectral lines – first towards the blue wavelength range, then back towards the red. If we analyze this movement of the spectral lines quantitatively, what is known as the radial-velocity curve can be derived from it. This yields parameters for the planetary orbit and the maximum mass of the planetary candidates. If the latter is less than the mass that a heavenly body requires to initiate thermonuclear fusion, the body is regarded as a planet.

The transit method works if the orbit of the planet is such that, when viewed from the Earth, it passes in front of the star. During the planet’s passage across the star disk, known as a transit, the planet’s presence reduces the amount of radiation from the stellar disc that reaches the observer and a decrease in the apparent brightness of the star can be measured. The radius of the planet and its density can be calculated from these measurements together with other data (such as the distance of the star from Earth) – astronomers then know whether the planet in question is a rocky planet or a gas planet. Such findings are incorporated into models of how planets are formed and help us to better understand how planetary systems develop.

German Aerospace Center