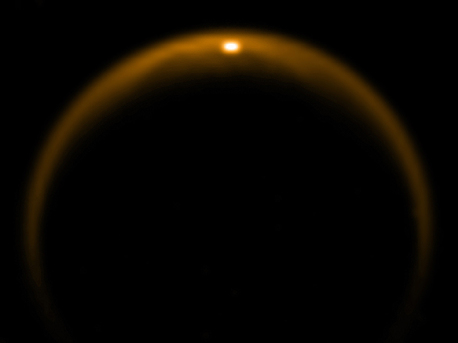

Reflecting surface of a lake on Titan

Sparkly Titan

© NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/DLR

|

This image shows the first flash of sunlight reflected off a lake on Saturn's moon Titan. The glint off a mirror-like surface is known as a specular reflection. The Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) on NASA's Cassini spacecraft detected this glint on 8 July 2009. It confirmed the presence of liquid in the moon's northern hemisphere, where lakes are more numerous and larger than those in the southern hemisphere. Scientists using VIMS had confirmed the presence of liquid in Ontario Lacus, the largest lake in the southern hemisphere, in 2008.

Reflections from a mirror-like liquid surface at infrared wavelengths

During the 59th flyby of Titan on 8 July 2009, Cassini's Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) observed a very bright, infrared glint, similar to visible glints of sunlight off Earth's bodies of liquid water, from an area in Titan's northern polar region. "We think that in nature only the surface of a liquid can appear so smooth," Dr Stephan explains. "An icy surface - even though it might be mirror-like after freezing - will become rougher from erosion and the grinding effect of tiny particles, or the deposition of atmospheric constituents," Prof Jaumann adds.

The image was taken at a wavelength of five microns (less than a ten thousandths of an inch) and at a spacecraft distance of about 120,000 miles, resulting in an image resolution of about 60 miles per pixel.

With a diameter of 3,220 miles, Titan is the largest moon of Saturn, the ringed planet. It is the only satellite in the Solar System surrounded by a dense atmosphere obscuring any direct view of its surface. With spectrometers, though, it is possible to peek through the cloud and haze shrouded atmosphere of Titan through what are called 'atmospheric windows' to get some idea about the icy surface, which is at minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit.

In comparison with radar images, the observation strongly points to a specular reflection from a smooth surface, close to the southern shoreline of Kraken Mare located in the northern hemisphere at 71° N and 337° W. Only where the viewing geometry is such that the specular point (mirror reflection point) falls onto one of the radar-dark surfaces do the VIMS observations show significant specular reflection. Ralf Jaumann points out that: "As VIMS observed the specular reflection just at the bright/dark boundary seen in the radar image acquired in 2006, the observation confirms the shoreline of Kraken Mare has been stable for the last three years, and the observation also suggests that the entire Kraken Mare basin is filled with liquid."

The VIMS science team has concluded that liquid hydrocarbons like methane or ethane exist. These substances are liquid even at the freezing-cold temperatures on Titan. Rivers were identified, likely fed by precipitation. Along the course of the drainage systems, deeply incised valleys erode in the icy landscape of Titan. Therefore it was immediate possible to guess that these streams of hydrocarbons end up in lakes.

Source: German Aerospace Center

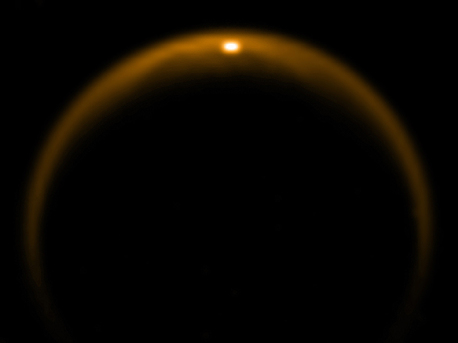

Reflecting surface of a lake on Titan

Sparkly Titan

© NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/DLR

|

This image shows the first flash of sunlight reflected off a lake on Saturn's moon Titan. The glint off a mirror-like surface is known as a specular reflection. The Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) on NASA's Cassini spacecraft detected this glint on 8 July 2009. It confirmed the presence of liquid in the moon's northern hemisphere, where lakes are more numerous and larger than those in the southern hemisphere. Scientists using VIMS had confirmed the presence of liquid in Ontario Lacus, the largest lake in the southern hemisphere, in 2008.

Reflections from a mirror-like liquid surface at infrared wavelengths

During the 59th flyby of Titan on 8 July 2009, Cassini's Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) observed a very bright, infrared glint, similar to visible glints of sunlight off Earth's bodies of liquid water, from an area in Titan's northern polar region. "We think that in nature only the surface of a liquid can appear so smooth," Dr Stephan explains. "An icy surface - even though it might be mirror-like after freezing - will become rougher from erosion and the grinding effect of tiny particles, or the deposition of atmospheric constituents," Prof Jaumann adds.

The image was taken at a wavelength of five microns (less than a ten thousandths of an inch) and at a spacecraft distance of about 120,000 miles, resulting in an image resolution of about 60 miles per pixel.

With a diameter of 3,220 miles, Titan is the largest moon of Saturn, the ringed planet. It is the only satellite in the Solar System surrounded by a dense atmosphere obscuring any direct view of its surface. With spectrometers, though, it is possible to peek through the cloud and haze shrouded atmosphere of Titan through what are called 'atmospheric windows' to get some idea about the icy surface, which is at minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit.

In comparison with radar images, the observation strongly points to a specular reflection from a smooth surface, close to the southern shoreline of Kraken Mare located in the northern hemisphere at 71° N and 337° W. Only where the viewing geometry is such that the specular point (mirror reflection point) falls onto one of the radar-dark surfaces do the VIMS observations show significant specular reflection. Ralf Jaumann points out that: "As VIMS observed the specular reflection just at the bright/dark boundary seen in the radar image acquired in 2006, the observation confirms the shoreline of Kraken Mare has been stable for the last three years, and the observation also suggests that the entire Kraken Mare basin is filled with liquid."

The VIMS science team has concluded that liquid hydrocarbons like methane or ethane exist. These substances are liquid even at the freezing-cold temperatures on Titan. Rivers were identified, likely fed by precipitation. Along the course of the drainage systems, deeply incised valleys erode in the icy landscape of Titan. Therefore it was immediate possible to guess that these streams of hydrocarbons end up in lakes.

Source: German Aerospace Center