General Relativiy Confirmed

Dark Matter is Matter of Fact

|

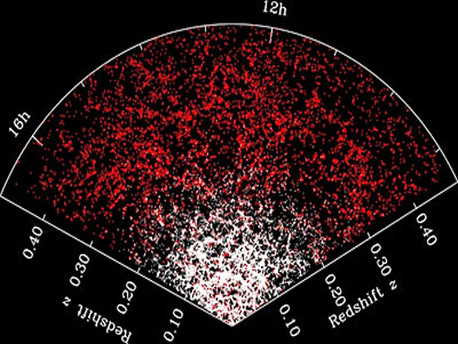

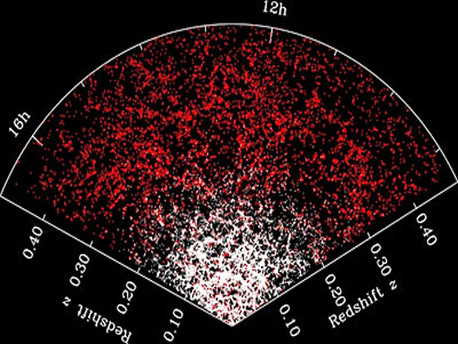

A partial map of the distribution of galaxies in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, going out to a distance of 7 billion light years. The amount of galaxy clustering that we observe today is a signature of how gravity acted over cosmic time, and allows as to test whether general relativity holds over these scales. (c) M. Blanton, Sloan Digital Sky Survey

- » 1 - Study Validates General Relativity On Cosmic Scale

- » 2 - Dark Matter

Study Validates General Relativity On Cosmic Scale

One major implication of the new study is that the existence of dark matter is the most likely explanation for the observation that galaxies and galaxy clusters move as if under the influence of some unseen mass, in addition to the stars astronomers observe.

"The nice thing about going to the cosmological scale is that we can test any full, alternative theory of gravity, because it should predict the things we observe," said co-author Uros Seljak, a professor at UC Berkeley. "Those alternative theories that do not require dark matter fail these tests."

In particular, the tensor-vector-scalar gravity (TeVeS) theory, which tweaks general relativity to avoid resorting to the existence of dark matter, fails the test.

The result conflicts with a report late last year that the very early universe, between 8 and 11 billion years ago, did deviate from the general relativistic description of gravity.

Einstein's General Theory of Relativity holds that gravity warps space and time, which means that light bends as it passes near a massive object, such as the core of a galaxy. The theory has been validated numerous times on the scale of the solar system, but tests on a galactic or cosmic scale have been inconclusive.

"There are some crude and imprecise tests of general relativity at galaxy scales, but we don't have good predictions for those tests from competing theories," Seljak said.

Such tests have become important in recent decades because the idea that some unseen mass permeates the universe disturbs some theorists and has spurred them to tweak general relativity to get rid of dark matter. TeVeS, for example, says that acceleration caused by the gravitational force from a body depends not only on the mass of that body, but also on the value of the acceleration caused by gravity.

General Relativiy Confirmed

Dark Matter is Matter of Fact

|

A partial map of the distribution of galaxies in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, going out to a distance of 7 billion light years. The amount of galaxy clustering that we observe today is a signature of how gravity acted over cosmic time, and allows as to test whether general relativity holds over these scales. (c) M. Blanton, Sloan Digital Sky Survey

- » 1 - Study Validates General Relativity On Cosmic Scale

- » 2 - Dark Matter

Study Validates General Relativity On Cosmic Scale

One major implication of the new study is that the existence of dark matter is the most likely explanation for the observation that galaxies and galaxy clusters move as if under the influence of some unseen mass, in addition to the stars astronomers observe.

"The nice thing about going to the cosmological scale is that we can test any full, alternative theory of gravity, because it should predict the things we observe," said co-author Uros Seljak, a professor at UC Berkeley. "Those alternative theories that do not require dark matter fail these tests."

In particular, the tensor-vector-scalar gravity (TeVeS) theory, which tweaks general relativity to avoid resorting to the existence of dark matter, fails the test.

The result conflicts with a report late last year that the very early universe, between 8 and 11 billion years ago, did deviate from the general relativistic description of gravity.

Einstein's General Theory of Relativity holds that gravity warps space and time, which means that light bends as it passes near a massive object, such as the core of a galaxy. The theory has been validated numerous times on the scale of the solar system, but tests on a galactic or cosmic scale have been inconclusive.

"There are some crude and imprecise tests of general relativity at galaxy scales, but we don't have good predictions for those tests from competing theories," Seljak said.

Such tests have become important in recent decades because the idea that some unseen mass permeates the universe disturbs some theorists and has spurred them to tweak general relativity to get rid of dark matter. TeVeS, for example, says that acceleration caused by the gravitational force from a body depends not only on the mass of that body, but also on the value of the acceleration caused by gravity.