Galaxy Clusters

Planck's first glimpse at galaxy clusters and a new supercluster

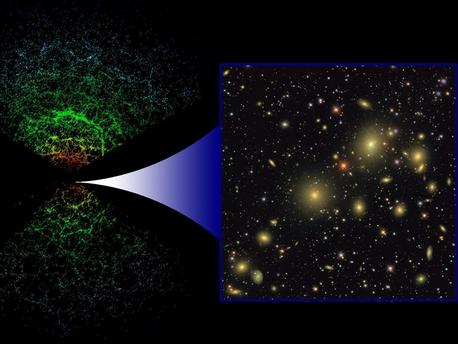

© Sloan Digital Sky Survey Team, NASA, NSF, DOE

|

This illustration depicts the large-scale distribution of galaxies as seen by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, an ambitious project that determined the distances of about one million galaxies. The two cones on the left of the image are a three dimensional (3D) map of the galaxies with the Earth at the centre. Going from the centre to the upper/lower edges of the map, more and more distant galaxies are seen, up to distances of about 2 thousand million light years. The colour of the galaxies is related to their luminosity. The clumpiness in the distribution of matter is clearly visible in this representation. The panel on the right shows a two dimensional (2D) image of galaxies in a small region of the sky. The 3D map is computed by combining the information contained in 2D images such as this one with an estimate of the distances of each individual object visible in it, derived from their spectra.

- » 1 - Surveying the microwave sky

- » 2 - The Coma cluster

- » 3 - A new supercluster, seen by Planck and XMM-Newton

Surveying the microwave sky

Planck's primary goal is to capture the most ancient light of the cosmos, the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), and for this purpose it boasts a superb set of nine frequency channels, spanning the spectral range from 30 to 857 GHz. Such a broad spectral coverage is not only instrumental in removing all sources of contamination from the CMB, in order to deliver what will be the sharpest image of the early Universe ever achieved - it also makes Planck an excellent hunter of galaxy clusters.

In fact, the nine frequency channels were carefully chosen by the Planck team with a particular phenomenon, known as the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich Effect (SZE), very much in mind. This effect describes the change of energy experienced by CMB photons when they encounter a galaxy cluster as they travel towards us, in the process imprinting a distinctive signature on the CMB itself. Hence, the SZE represents a unique tool to detect galaxy clusters, even at high redshift.

"As the fossil photons from the Big Bang cross the Universe, they interact with the matter that they encounter: when travelling through a galaxy cluster, for example, the CMB photons scatter off free electrons present in the hot gas that fills the cluster," explains Nabila Aghanim of the Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale in Orsay, France, a leading member of the group of Planck scientists investigating SZE clusters and secondary anisotropies. "These collisions redistribute the frequencies of photons in a particular way that enables us to isolate the intervening cluster from the CMB signal."

Since the hot electrons in the cluster are much more energetic than the CMB photons, interactions between the two species typically result in the photons being scattered to higher energies. This means that, when looking at the CMB in the direction of a galaxy cluster, one observes a deficit, with respect to the average CMB signal, of low-energy photons and a surplus of more energetic ones. The threshold frequency, separating deficit and surplus, corresponds to 217 GHz. Planck's channels probe the spectrum both below and above this threshold, with one of them centred exactly on 217 GHz.

Galaxy Clusters

Planck's first glimpse at galaxy clusters and a new supercluster

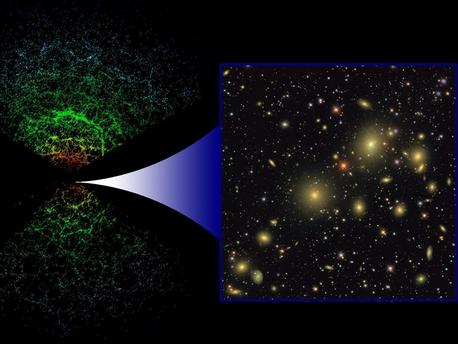

© Sloan Digital Sky Survey Team, NASA, NSF, DOE

|

This illustration depicts the large-scale distribution of galaxies as seen by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, an ambitious project that determined the distances of about one million galaxies. The two cones on the left of the image are a three dimensional (3D) map of the galaxies with the Earth at the centre. Going from the centre to the upper/lower edges of the map, more and more distant galaxies are seen, up to distances of about 2 thousand million light years. The colour of the galaxies is related to their luminosity. The clumpiness in the distribution of matter is clearly visible in this representation. The panel on the right shows a two dimensional (2D) image of galaxies in a small region of the sky. The 3D map is computed by combining the information contained in 2D images such as this one with an estimate of the distances of each individual object visible in it, derived from their spectra.

- » 1 - Surveying the microwave sky

- » 2 - The Coma cluster

- » 3 - A new supercluster, seen by Planck and XMM-Newton

Surveying the microwave sky

Planck's primary goal is to capture the most ancient light of the cosmos, the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), and for this purpose it boasts a superb set of nine frequency channels, spanning the spectral range from 30 to 857 GHz. Such a broad spectral coverage is not only instrumental in removing all sources of contamination from the CMB, in order to deliver what will be the sharpest image of the early Universe ever achieved - it also makes Planck an excellent hunter of galaxy clusters.

In fact, the nine frequency channels were carefully chosen by the Planck team with a particular phenomenon, known as the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich Effect (SZE), very much in mind. This effect describes the change of energy experienced by CMB photons when they encounter a galaxy cluster as they travel towards us, in the process imprinting a distinctive signature on the CMB itself. Hence, the SZE represents a unique tool to detect galaxy clusters, even at high redshift.

"As the fossil photons from the Big Bang cross the Universe, they interact with the matter that they encounter: when travelling through a galaxy cluster, for example, the CMB photons scatter off free electrons present in the hot gas that fills the cluster," explains Nabila Aghanim of the Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale in Orsay, France, a leading member of the group of Planck scientists investigating SZE clusters and secondary anisotropies. "These collisions redistribute the frequencies of photons in a particular way that enables us to isolate the intervening cluster from the CMB signal."

Since the hot electrons in the cluster are much more energetic than the CMB photons, interactions between the two species typically result in the photons being scattered to higher energies. This means that, when looking at the CMB in the direction of a galaxy cluster, one observes a deficit, with respect to the average CMB signal, of low-energy photons and a surplus of more energetic ones. The threshold frequency, separating deficit and surplus, corresponds to 217 GHz. Planck's channels probe the spectrum both below and above this threshold, with one of them centred exactly on 217 GHz.