Galaxy Clusters

The Coma cluster

© Planck image: ESA/ LFI & HFI Consortia; ROSAT image: Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik; DSS image: NASA, ESA, and the Digitized Sky Survey 2. Acknowledgment: Davide De Martin (ESA/Hubble)

|

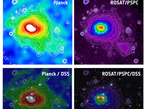

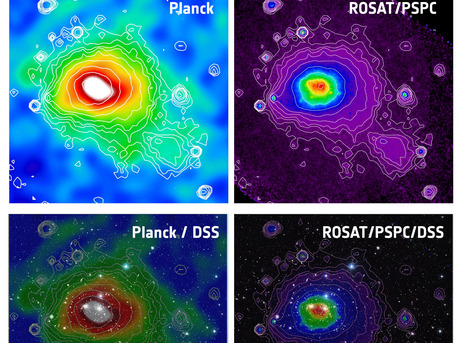

These images of the Coma cluster (also known as Abell 1656), a very hot and nearby cluster of galaxies, show how it appears through the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich Effect (top left) and X-ray emission (top right). The top-left panel shows the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich image of the Coma cluster produced by Planck, and the top-right panel shows the same cluster imaged in X-rays by the ROSAT satellite. The colours in both images map the intensity of the measured signals. The X-ray contours are also superimposed on the Planck image as a visual aid. As a comparison, the images are shown superimposed on a wide-field optical image of the Coma cluster from the Digitised Sky Survey in the two lower panels. Located at a distance of about 300 million light-years from us, the Coma cluster extends over more than two degrees on the sky, corresponding to over 4 times the angular size of the full Moon. This image of the Coma cluster highlights Planck's ability to observe objects on very large scales, thanks to its all-sky survey strategy. The region depicted in each image is slightly larger than 2 degrees.

Planck's design, optimised for detecting the SZE signal from clusters scattered throughout the sky, is however not suited for in-depth investigations— its resolution is simply not sufficient to discern much detail for most of them, especially any newly discovered, high-redshift ones. Observations at other wavelengths are necessary to pin down the details of these massive structures. Since the hot gas in galaxy clusters emits copious amounts of X-rays, observations in this spectral band prove particularly useful as they probe the very same component responsible for producing the SZE.

In order to confirm their identity, Planck's cluster candidates are compared with existing catalogues of clusters, like the ROSAT all-sky X-ray catalogue of clusters. When the Planck candidates do not correspond to any known structure, and after careful quality checks of the SZ signal, they may become the target of brand new, follow-up observations with ESA's X-ray observatory, XMM-Newton.

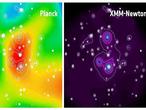

"With its exceptional sensitivity, XMM-Newton is the ideal partner to follow-up the sources detected by Planck via the SZE," says Monique Arnaud, from the Service d'Astrophysique, Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique, France, who leads the Planck group following up sources with XMM-Newton. It is the special synergy between these two ESA missions that has allowed astronomers to use snapshot XMM-Newton observations to confirm that Planck's first detections are indeed clusters, and has revealed an even larger structure: a supercluster of galaxies.

Galaxy Clusters

The Coma cluster

© Planck image: ESA/ LFI & HFI Consortia; ROSAT image: Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik; DSS image: NASA, ESA, and the Digitized Sky Survey 2. Acknowledgment: Davide De Martin (ESA/Hubble)

|

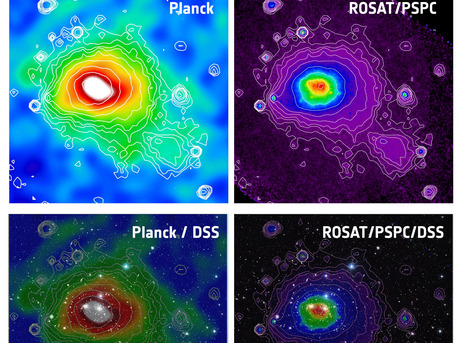

These images of the Coma cluster (also known as Abell 1656), a very hot and nearby cluster of galaxies, show how it appears through the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich Effect (top left) and X-ray emission (top right). The top-left panel shows the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich image of the Coma cluster produced by Planck, and the top-right panel shows the same cluster imaged in X-rays by the ROSAT satellite. The colours in both images map the intensity of the measured signals. The X-ray contours are also superimposed on the Planck image as a visual aid. As a comparison, the images are shown superimposed on a wide-field optical image of the Coma cluster from the Digitised Sky Survey in the two lower panels. Located at a distance of about 300 million light-years from us, the Coma cluster extends over more than two degrees on the sky, corresponding to over 4 times the angular size of the full Moon. This image of the Coma cluster highlights Planck's ability to observe objects on very large scales, thanks to its all-sky survey strategy. The region depicted in each image is slightly larger than 2 degrees.

Planck's design, optimised for detecting the SZE signal from clusters scattered throughout the sky, is however not suited for in-depth investigations— its resolution is simply not sufficient to discern much detail for most of them, especially any newly discovered, high-redshift ones. Observations at other wavelengths are necessary to pin down the details of these massive structures. Since the hot gas in galaxy clusters emits copious amounts of X-rays, observations in this spectral band prove particularly useful as they probe the very same component responsible for producing the SZE.

In order to confirm their identity, Planck's cluster candidates are compared with existing catalogues of clusters, like the ROSAT all-sky X-ray catalogue of clusters. When the Planck candidates do not correspond to any known structure, and after careful quality checks of the SZ signal, they may become the target of brand new, follow-up observations with ESA's X-ray observatory, XMM-Newton.

"With its exceptional sensitivity, XMM-Newton is the ideal partner to follow-up the sources detected by Planck via the SZE," says Monique Arnaud, from the Service d'Astrophysique, Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique, France, who leads the Planck group following up sources with XMM-Newton. It is the special synergy between these two ESA missions that has allowed astronomers to use snapshot XMM-Newton observations to confirm that Planck's first detections are indeed clusters, and has revealed an even larger structure: a supercluster of galaxies.