Cassini Sees

Saturn on a Cosmic Dimmer Switch

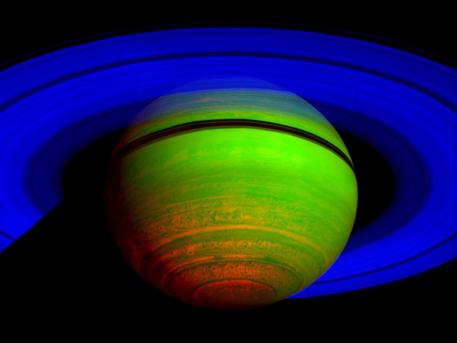

© NASA/JPL/ASI/University of Arizona

|

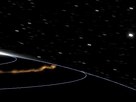

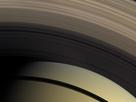

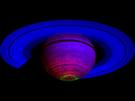

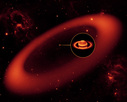

This false-color composite image, constructed from data obtained by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, shows Saturn's rings and southern hemisphere. The composite image was made from 65 individual observations by Cassini's visual and infrared mapping spectrometer in the near-infrared portion of the light spectrum on Nov. 1, 2008. The observations were each six minutes long.

"The fact that Saturn actually emits more than twice the energy it absorbs from the sun has been a puzzle for many decades now," said Kevin Baines, a Cassini team scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., and a co-author on a new paper about Saturn's energy output. "What generates that extra energy? This paper represents the first step in that analysis."

The research, reported this week in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets, was led by Liming Li of Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. (now at the University of Houston).

"The Cassini CIRS data are very valuable because they give us a nearly complete picture of Saturn," Li said. "This is the only single data set that provides so much information about this planet, and it's the first time that anybody has been able to study the power emitted by one of the giant planets in such detail."

The planets in our solar system lose energy in the form of heat radiation in wavelengths that are invisible to the human eye. The CIRS instrument picks up wavelengths in the thermal infrared region, far enough beyond red light where the wavelengths correspond to heat emission.

"In planetary science, we tend to think of planets as losing power evenly in all directions and at a steady rate," Li said. "Now we know Saturn is not doing that." (Power is the amount of energy emitted per unit of time.)

Instead, Saturn's flow of outgoing energy was lopsided, with its southern hemisphere giving off about one-sixth more energy than the northern one, Li explains. This effect matched Saturn's seasons: during those five Earth-years, it was summer in the southern hemisphere and winter in the northern one. (A season on Saturn lasts about seven Earth-years.) Like Earth, Saturn has these seasons because the planet is tilted on its axis, so one hemisphere receives more energy from the sun and experiences summer, while the other receives less energy and is shrouded in winter. Saturn's equinox, when the sun was directly over the equator, occurred in August 2009.

In the study, Saturn's seasons looked Earth-like in another way: in each hemisphere, its effective temperature, which characterizes its thermal emission to space, started to warm up or cool down as a change of season approached. The effective temperature provides a simple way to track the response of Saturn's atmosphere to the seasonal changes, which is complicated because Saturn's weather is variable and the atmosphere tends to retain heat. Cassini's observations revealed that the effective temperature in the northern hemisphere gradually dropped from 2005 to 2008 and started to warm up again by 2009. In the southern hemisphere, the effective temperature cooled from 2005 to 2009.

The emitted energy for each hemisphere rose and fell along with the effective temperature. Even so, during this five-year period, the planet as a whole seemed to be slowly cooling down and emitting less energy.

To find out if similar changes were happening one Saturn-year ago, the researchers looked at data collected by the Voyager spacecraft in 1980 and 1981 and did not see the imbalance between the southern and northern hemispheres. Instead, the two regions were much more consistent with each other.

Why wouldn't Voyager have seen the same summer-versus-winter difference between the two hemispheres? One explanation is that cloud patterns at depth could have fluctuated, blocking and scattering infrared light differently.

"It's reasonable to think that the changes in Saturn's emitted power are related to cloud cover," says Amy Simon-Miller, who heads the Planetary Systems Laboratory at Goddard and is a co-author on the paper. "As the amount of cloud cover changes, the amount of radiation escaping into space also changes. This might vary during a single season and from one Saturn-year to another. But to fully understand what is happening on Saturn, we will need the other half of the picture: the amount of power being absorbed by the planet."

Scientists will be doing that as a next step by comparing the instrument's findings to data obtained by Cassini's imaging cameras and infrared mapping spectrometer instrument. The spectrometer, in particular, measures the amount of sunlight reflected by Saturn. Because scientists know the total amount of solar energy delivered to Saturn, they can derive the amount of sunlight absorbed by the planet and discern how much heat the planet itself is emitting. These calculations help scientists tackle what the actual source of that warming might be and whether it changes.

Better understanding Saturn's internal heat flow "will significantly deepen our understanding of the weather, internal structure and evolution of Saturn and the other giant planets," Li said.

Source: NASA

Cassini Sees

Saturn on a Cosmic Dimmer Switch

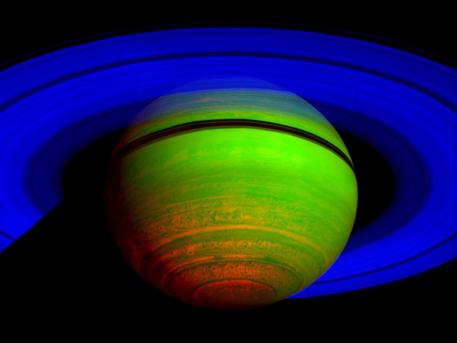

© NASA/JPL/ASI/University of Arizona

|

This false-color composite image, constructed from data obtained by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, shows Saturn's rings and southern hemisphere. The composite image was made from 65 individual observations by Cassini's visual and infrared mapping spectrometer in the near-infrared portion of the light spectrum on Nov. 1, 2008. The observations were each six minutes long.

"The fact that Saturn actually emits more than twice the energy it absorbs from the sun has been a puzzle for many decades now," said Kevin Baines, a Cassini team scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., and a co-author on a new paper about Saturn's energy output. "What generates that extra energy? This paper represents the first step in that analysis."

The research, reported this week in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets, was led by Liming Li of Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. (now at the University of Houston).

"The Cassini CIRS data are very valuable because they give us a nearly complete picture of Saturn," Li said. "This is the only single data set that provides so much information about this planet, and it's the first time that anybody has been able to study the power emitted by one of the giant planets in such detail."

The planets in our solar system lose energy in the form of heat radiation in wavelengths that are invisible to the human eye. The CIRS instrument picks up wavelengths in the thermal infrared region, far enough beyond red light where the wavelengths correspond to heat emission.

"In planetary science, we tend to think of planets as losing power evenly in all directions and at a steady rate," Li said. "Now we know Saturn is not doing that." (Power is the amount of energy emitted per unit of time.)

Instead, Saturn's flow of outgoing energy was lopsided, with its southern hemisphere giving off about one-sixth more energy than the northern one, Li explains. This effect matched Saturn's seasons: during those five Earth-years, it was summer in the southern hemisphere and winter in the northern one. (A season on Saturn lasts about seven Earth-years.) Like Earth, Saturn has these seasons because the planet is tilted on its axis, so one hemisphere receives more energy from the sun and experiences summer, while the other receives less energy and is shrouded in winter. Saturn's equinox, when the sun was directly over the equator, occurred in August 2009.

In the study, Saturn's seasons looked Earth-like in another way: in each hemisphere, its effective temperature, which characterizes its thermal emission to space, started to warm up or cool down as a change of season approached. The effective temperature provides a simple way to track the response of Saturn's atmosphere to the seasonal changes, which is complicated because Saturn's weather is variable and the atmosphere tends to retain heat. Cassini's observations revealed that the effective temperature in the northern hemisphere gradually dropped from 2005 to 2008 and started to warm up again by 2009. In the southern hemisphere, the effective temperature cooled from 2005 to 2009.

The emitted energy for each hemisphere rose and fell along with the effective temperature. Even so, during this five-year period, the planet as a whole seemed to be slowly cooling down and emitting less energy.

To find out if similar changes were happening one Saturn-year ago, the researchers looked at data collected by the Voyager spacecraft in 1980 and 1981 and did not see the imbalance between the southern and northern hemispheres. Instead, the two regions were much more consistent with each other.

Why wouldn't Voyager have seen the same summer-versus-winter difference between the two hemispheres? One explanation is that cloud patterns at depth could have fluctuated, blocking and scattering infrared light differently.

"It's reasonable to think that the changes in Saturn's emitted power are related to cloud cover," says Amy Simon-Miller, who heads the Planetary Systems Laboratory at Goddard and is a co-author on the paper. "As the amount of cloud cover changes, the amount of radiation escaping into space also changes. This might vary during a single season and from one Saturn-year to another. But to fully understand what is happening on Saturn, we will need the other half of the picture: the amount of power being absorbed by the planet."

Scientists will be doing that as a next step by comparing the instrument's findings to data obtained by Cassini's imaging cameras and infrared mapping spectrometer instrument. The spectrometer, in particular, measures the amount of sunlight reflected by Saturn. Because scientists know the total amount of solar energy delivered to Saturn, they can derive the amount of sunlight absorbed by the planet and discern how much heat the planet itself is emitting. These calculations help scientists tackle what the actual source of that warming might be and whether it changes.

Better understanding Saturn's internal heat flow "will significantly deepen our understanding of the weather, internal structure and evolution of Saturn and the other giant planets," Li said.

Source: NASA