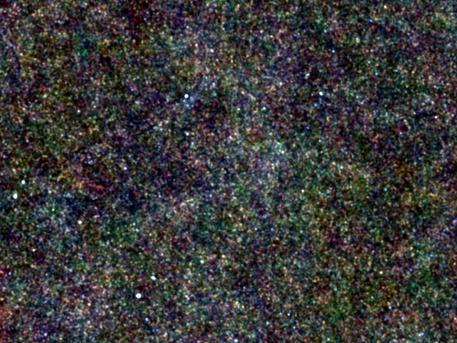

Lockman Hole

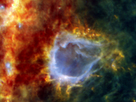

Herschel Measures Dark Matter for Star-Forming Galaxies

© ESA/Herschel/SPIRE/HerMES |

A region of the sky called the "Lockman Hole," located in the constellation of Ursa Major, is one of the areas surveyed in infrared light by the Herschel Space Observatory. All of the little dots in this picture are distant galaxies. The pattern of their collective light is what's known as the cosmic infrared background. By studying this pattern, astronomers were able to measure how much dark matter it takes to create a galaxy bursting with young stars. Regions like this one are almost completely devoid of objects in our Milky Way galaxy, making them ideal for astronomers studying galaxies in the distant universe.

"If you start with too little dark matter, then a developing galaxy would peter out," said astronomer Asantha Cooray of the University of California, Irvine. He is the principal investigator of new research appearing in the journal Nature, online on Feb. 16 and in the Feb. 24 print edition. "If you have too much, then gas doesn't cool efficiently to form one large galaxy, and you end up with lots of smaller galaxies. But if you have the just the right amount of dark matter, then a galaxy bursting with stars will pop out."

The right amount of dark matter turns out to be a mass equivalent to 300 billion of our suns.

Herschel launched into space in May 2009. The mission's large, 3.5-meter (11.5-foot) telescope detects longer-wavelength infrared light from a host of objects, ranging from asteroids and planets in our own solar system to faraway galaxies.

"This remarkable discovery shows that early galaxies go through periods of star formation much more vigorous than in our present-day Milky Way," said William Danchi, Herschel program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "It showcases the importance of infrared astronomy, enabling us to peer behind veils of interstellar dust to see stars in their infancy."

Cooray and colleagues used the telescope to measure infrared light from massive, star-forming galaxies located 10 to 11 billion light-years away. Astronomers think these and other galaxies formed inside clumps of dark matter, similar to chicks incubating in eggs.

Giant clumps of dark matter act like gravitational wells that collect the gas and dust needed for making galaxies. When a mixture of gas and dust falls into a well, it condenses and cools, allowing new stars to form. Eventually enough stars form, and a galaxy is born.

Herschel was able to uncover more about how this galaxy-making process works by mapping the infrared light from collections of very distant, massive star-forming galaxies. This pattern of light, called the cosmic infrared background, is like a web that spreads across the sky. Because Herschel can survey large areas quickly with high resolution, it was able to create the first detailed maps of the cosmic infrared background.

"It turns out that it's much more effective to look at these patterns rather than the individual galaxies," said Jamie Bock of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Bock is the U.S. principal investigator for Herschel's Spectral and Photometric Imaging Receiver instrument used to make the maps. "This is like looking at a picture in a magazine from a reading distance. You don't notice the individual dots, but you see the big picture. Herschel gives us the big picture of these distant galaxies, showing the influence of dark matter."

The maps showed the galaxies are more clustered into groups than previously believed. The amount of galaxy clustering depends on the amount of dark matter. After a series of complicated numerical simulations, the astronomers were able to determine exactly how much dark matter is needed to form a single star-forming galaxy.

"This measurement is important, because we are homing in on the very basic ingredients in galaxy formation," said Alexandre Amblard of UC Irvine, first author of the Nature paper. "In this case, the ingredient, dark matter, happens to be an exotic substance that we still have much to learn about."

Source: NASA

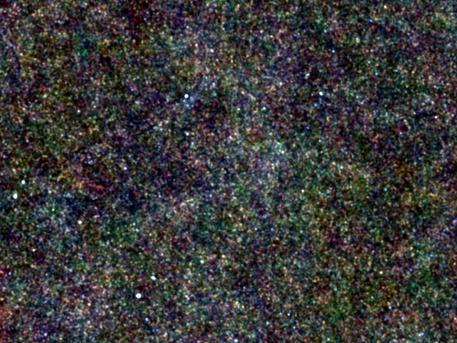

Lockman Hole

Herschel Measures Dark Matter for Star-Forming Galaxies

© ESA/Herschel/SPIRE/HerMES |

A region of the sky called the "Lockman Hole," located in the constellation of Ursa Major, is one of the areas surveyed in infrared light by the Herschel Space Observatory. All of the little dots in this picture are distant galaxies. The pattern of their collective light is what's known as the cosmic infrared background. By studying this pattern, astronomers were able to measure how much dark matter it takes to create a galaxy bursting with young stars. Regions like this one are almost completely devoid of objects in our Milky Way galaxy, making them ideal for astronomers studying galaxies in the distant universe.

"If you start with too little dark matter, then a developing galaxy would peter out," said astronomer Asantha Cooray of the University of California, Irvine. He is the principal investigator of new research appearing in the journal Nature, online on Feb. 16 and in the Feb. 24 print edition. "If you have too much, then gas doesn't cool efficiently to form one large galaxy, and you end up with lots of smaller galaxies. But if you have the just the right amount of dark matter, then a galaxy bursting with stars will pop out."

The right amount of dark matter turns out to be a mass equivalent to 300 billion of our suns.

Herschel launched into space in May 2009. The mission's large, 3.5-meter (11.5-foot) telescope detects longer-wavelength infrared light from a host of objects, ranging from asteroids and planets in our own solar system to faraway galaxies.

"This remarkable discovery shows that early galaxies go through periods of star formation much more vigorous than in our present-day Milky Way," said William Danchi, Herschel program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "It showcases the importance of infrared astronomy, enabling us to peer behind veils of interstellar dust to see stars in their infancy."

Cooray and colleagues used the telescope to measure infrared light from massive, star-forming galaxies located 10 to 11 billion light-years away. Astronomers think these and other galaxies formed inside clumps of dark matter, similar to chicks incubating in eggs.

Giant clumps of dark matter act like gravitational wells that collect the gas and dust needed for making galaxies. When a mixture of gas and dust falls into a well, it condenses and cools, allowing new stars to form. Eventually enough stars form, and a galaxy is born.

Herschel was able to uncover more about how this galaxy-making process works by mapping the infrared light from collections of very distant, massive star-forming galaxies. This pattern of light, called the cosmic infrared background, is like a web that spreads across the sky. Because Herschel can survey large areas quickly with high resolution, it was able to create the first detailed maps of the cosmic infrared background.

"It turns out that it's much more effective to look at these patterns rather than the individual galaxies," said Jamie Bock of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Bock is the U.S. principal investigator for Herschel's Spectral and Photometric Imaging Receiver instrument used to make the maps. "This is like looking at a picture in a magazine from a reading distance. You don't notice the individual dots, but you see the big picture. Herschel gives us the big picture of these distant galaxies, showing the influence of dark matter."

The maps showed the galaxies are more clustered into groups than previously believed. The amount of galaxy clustering depends on the amount of dark matter. After a series of complicated numerical simulations, the astronomers were able to determine exactly how much dark matter is needed to form a single star-forming galaxy.

"This measurement is important, because we are homing in on the very basic ingredients in galaxy formation," said Alexandre Amblard of UC Irvine, first author of the Nature paper. "In this case, the ingredient, dark matter, happens to be an exotic substance that we still have much to learn about."

Source: NASA