International Space Station

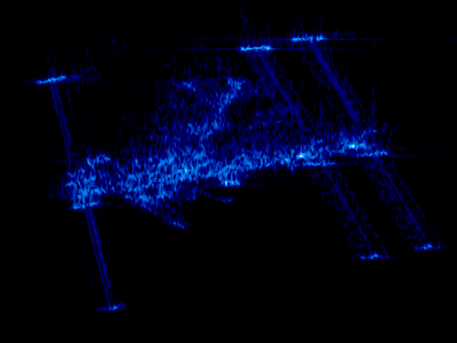

Radar Image Of The ISS

© DLR

|

In contrast to optical cameras, radar does not ‘see’ surfaces. Instead, it is much more aware of the edges and corners which bounce back the microwave signal it transmits.

Radar image of the ISS

In contrast to optical cameras, radar does not 'see' surfaces. Instead, the mirowave signals transmitted by the radar are reflected back much more intensely by edges and corners. Smooth surfaces such as those on the solar power generators of the ISS or the radiator panels used to dissipate excess heat, unless directly facing the radar antenna, tend to deflect rather than reflect the radar beam, causing these features to appear as dark areas on the radar image. The radar image of the ISS therefore looks like a dense collection of bright spots from which the outlines of the Space Station can be identified clearly. The central element on the ISS, to which all the modules are docked, has a lattice grid structure with several surfaces to reflect the radar beam, making it readily identifiable.

This image has a resolution of about three feet. In other words, objects can be depicted as discrete units - that is, shown separately – provided that they are at least three feet apart. If they are closer together, they tend to merge into a single block on a radar image. However, if they have good reflective properties, objects measuring less than three feet can be portrayed effectively. Having said that, the radar image will always enlarge them to at least three feet – there being no way around the laws of physics in this case.

Source: German Aerospace Center

International Space Station

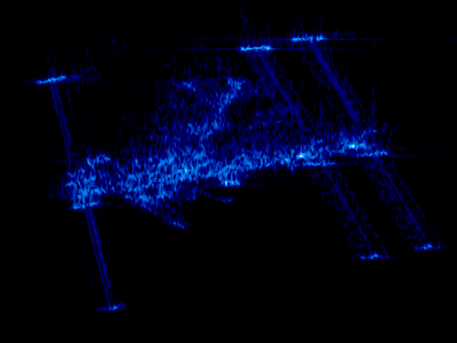

Radar Image Of The ISS

© DLR

|

In contrast to optical cameras, radar does not ‘see’ surfaces. Instead, it is much more aware of the edges and corners which bounce back the microwave signal it transmits.

Radar image of the ISS

In contrast to optical cameras, radar does not 'see' surfaces. Instead, the mirowave signals transmitted by the radar are reflected back much more intensely by edges and corners. Smooth surfaces such as those on the solar power generators of the ISS or the radiator panels used to dissipate excess heat, unless directly facing the radar antenna, tend to deflect rather than reflect the radar beam, causing these features to appear as dark areas on the radar image. The radar image of the ISS therefore looks like a dense collection of bright spots from which the outlines of the Space Station can be identified clearly. The central element on the ISS, to which all the modules are docked, has a lattice grid structure with several surfaces to reflect the radar beam, making it readily identifiable.

This image has a resolution of about three feet. In other words, objects can be depicted as discrete units - that is, shown separately – provided that they are at least three feet apart. If they are closer together, they tend to merge into a single block on a radar image. However, if they have good reflective properties, objects measuring less than three feet can be portrayed effectively. Having said that, the radar image will always enlarge them to at least three feet – there being no way around the laws of physics in this case.

Source: German Aerospace Center